2024 Annual Report

A Year of Transition and Continued Progress

Matt Sanders, Interim Director of Public Defense

DPD is at the forefront of shaping the future of public defense, embracing our role as pioneers committed to sustainable workloads and exceptional advocacy. We are dedicated to establishing a national model, creating a comprehensive framework from which other public defense agencies may draw inspiration.

The year 2024 marked a pivotal moment in this ongoing effort, as Anita Khandelwal concluded her impactful six-year tenure as Director in September, leaving behind a strengthened and nationally recognized department. In October, I had the privilege of stepping into this role, initially as Interim Director, ensuring continuity and stability during a critical moment of transition.

Throughout 2024, we worked together to navigate significant changes with resilience. We achieved key policy victories, modernized staffing and caseload management practices, and laid a strong foundation to continue our positive contributions to the King County community. Most importantly, we positioned ourselves to build upon our commitment to high-quality advocacy from 2024 into 2025 and beyond— continuing to defend our clients' rights, protect them from constitutional violations, and uphold the inherent dignity and humanity of every person DPD represents.

DPD Employees Serving Our Community in 2024

In 2024, DPD served 16,491 clients across our diverse practice areas, consistently providing exceptional advocacy and securing life-changing outcomes. This annual report shares stories and examples of the remarkable work performed daily by DPD’s managing attorneys, supervisors, attorneys, mitigation specialists, investigators, paralegals, and legal assistants.

From obtaining acquittals for clients wrongfully charged with serious offenses, preserving family integrity by keeping children safely with their parents, advocating fiercely for vulnerable individuals facing involuntary civil commitment, to numerous other meaningful victories for our clients—our dedicated employees continue to make a positive difference in King County’s community. This annual report highlights some, though certainly not all, of the extraordinary DPD employees who dedicate themselves to this critical and noble work.

Significant Department Milestones of 2024

Throughout 2024, DPD accomplished several pivotal milestones:

- Introduced a fall class of thirty-two new attorneys.

- Successfully advocated for the WSBA’s adoption of groundbreaking revised caseload standards, laying the foundation for a significant statewide policy shift toward more manageable workloads and improved representation for clients.

- Released a new department-wide case management system that integrated a sophisticated case-weight tracking system aligned with the new caseload standards well in advance of Phase 1, beginning July 2, 2025.

- Transitioned to new departmental leadership, maintaining stability and continuity during a crucial period.

- Achieved substantial legislative victories, enhancing protections for clients across our practice areas to advance individual rights and address systemic inequities.

- Updated internal staffing models to reflect the WSBA’s new caseload standards and secured approval from the King County Council for additional attorney positions, proactively establishing a sustainable infrastructure for meeting future caseload demands.

Overcoming Challenges from 2024

Despite significant achievements, 2024 presented notable challenges, including attorney attrition, unprecedented caseload pressures, and complexities associated with operationalizing the WSBA caseload standards. Recognizing these pressures, DPD proactively engaged in comprehensive strategic planning, advocacy, and targeted recruitment efforts.

Responding directly to these challenges has already yielded early successes in 2025, including:

- Record-setting recruitment efforts, boosted by hiring DPD's first-ever dedicated attorney recruiter.

- Historic staffing levels in our felony practice areas, achieved by early 2025.

- Preparations for welcoming our largest-ever incoming class, consisting of 48 new attorneys in fall 2025.

These immediate successes affirm the effectiveness of our proactive approach and strategic preparations from 2024.

Looking Forward to 2025 with Confidence

Reflecting on 2024, we have every reason to feel optimistic about DPD’s future. Our deliberate and strategic efforts last year have already begun delivering measurable results. Moving forward, our focus remains clear:

- Successfully implementing Phase 1 of the WSBA’s new caseload standards, ensuring sustainable workloads and excellent advocacy.

- Investing heavily in standardized professional training and development opportunities for all DPD staff, ensuring we develop strong advocates and robust defense teams.

- Creating professional development and career pathways for DPD professional staff.

- Further strengthening partnerships with SEIU 925 and Teamsters Local 117, reinforcing workplace equity, fairness, and employee well-being.

Every day, I am inspired by the exceptional people at DPD who, through their dedication, passion, and advocacy, consistently turn noble efforts into the daily routine—whether it's defending clients in court, reuniting families, or advocating for the most vulnerable members of our community. Their unwavering commitment to our clients motivates me to ensure they have the resources, support, and encouragement they need to continue their essential work. It is because of their commitment— and our shared vision—that I am confident DPD’s brightest days lie ahead.

— Matt Sanders, Director, King County Department of Public Defense

Honoring Director Khandelwal's Legacy

Former Director Anita Khandelwal, who led DPD from 2018 to 2024.

Simply put, DPD would not be a nationally recognized public defense office without the leadership of Anita Khandelwal. Serving as the department’s Director from 2018 to 2024, she oversaw DPD’s transformation from a fledgling public agency to an unparalleled force for wringing some semblance of fairness out of the criminal legal system – all while cementing the autonomy from political interference DPD needs to fight for our clients’ rights without reservation.

During her tenure, Director Khandelwal established DPD as a destination public defense office for top law students from across the country including those from our backyard at UW and Seattle U. With her unflinching commitment to speaking truth to power as the head of our department, she ensured DPD’s public defenders and non-attorney professionals had every resource they needed to provide exceptional representation to every single client.

When other actors in the criminal legal system refused to respect our clients’ rights, Director Khandelwal pursued impact litigation – even against other County entities – to remedy those injustices. She sued Seattle Municipal Court to force compliance with court rules requiring timely hearings for in-custody clients seeking pre-trial release, challenged King County Superior Court’s practice of changing pre-trial release conditions for clients facing felony charges ex parte, and fought all the way to our state’s Supreme Court to give meaning to caseload limits for public defenders in Involuntary Treatment Act court.

Her legacy stretches beyond DPD’s reputation for outstanding individual representation in criminal and civil defense; as Director, she assembled a team of exceptional advocates and policy experts who made transformative changes to the systems that seek to oppress DPD’s clients. In civil practice, DPD’s policy team collaborated with community partners to make the standard for removing a child from their parent codified in the Indian Child Welfare Act – widely recognized as the gold standard in family defense – apply to all emergency removal proceedings in the state. On criminal issues, DPD passed local and state laws protecting children’s Miranda rights during custodial interrogations from police and chipped away at countless other unjust ways in which the criminal legal system is biased against our clients.

DPD is where it is today due to the work of Anita Khandelwal and her courage, compassion, and vision. As the department enters a new era defined by the first-in-the-nation caseload standards she helped advocate for, Director Khandelwal’s legacy will long outlast her tenure as the King County Public Defender.

Unwavering Advocacy: A Year of Exceptional Representation Despite Crushing Caseloads

Selena Alonzo, an attorney at DPD who represents clients facing felony charges.

Even as the increasingly unsustainable nature of criminal caseloads in public defense took center stage in 2024, DPD’s defense teams conducted a breakneck pace of trials while negotiating resolutions for thousands of clients facing felony charges. Through countless hours of hard work and compassionate advocacy, the department’s attorneys, investigators, mitigation specialists, paralegals and legal assistants fought to defend their clients’ dignity in a system stacked in the government’s favor at every turn.

They freed clients from coercive pretrial incarceration and crafted release plans to prevent people from leaving jail without support, negotiated reductions in charges or persuaded prosecutors to dismiss them entirely, and won not guilty verdicts for clients who often waited years for their day in court.

Despite the frustrating delays brought on by a system clogged with unnecessary felony filings, attorneys like Selena Alonzo cherish the chance to make a lasting impact on the life of a client. “The whole reason I stay in this work is for moments when a client tells me I changed his thinking about public defenders,” she said.

Drawing on the experience of DPD’s defense teams and clients, the department partnered with community-based organizations to reduce some of the harm of the criminal legal system by advancing legislation, proposing court rule amendments, and litigating over crucial issues affecting our clients’ rights.

Inefficient Prosecution Compounds the Caseload Crisis

As part of DPD’s preparation for implementing the new caseload standards, the department began tracking the “case weight tier” for each newly assigned case when our new case management system launched in June 2024. As outlined in the WSBA caseload standards, each new felony case is assigned a weighted credit depending on the seriousness and complexity of the charge. Low-level felonies, like possession of stolen property in the second degree, are worth one credit while a murder case merits seven credits.

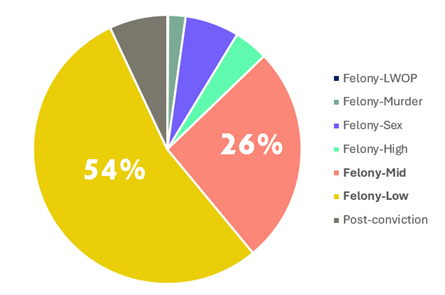

DPD analysis of felony assignments since July 2024 by case-weight tier

Our data capturing the case weight tiers for all new cases assigned to DPD since July 2024 shows that more than half of the felonies filed by the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office (PAO) over that time are low-level filings that only qualify for a single credit. The overwhelming flood of low-level felony filings, often with no allegations of interpersonal violence, clogs up Superior Court dockets and makes cases take longer and longer to resolve – even when clients are willing to accept a reasonable plea deal from prosecutors.

“I have 77 felony cases right now. The reason I have a lot of those is because I can't get any responses [from prosecutors],” said attorney Selena Alonzo. One case from this year stood out to her as an archetypical example of the costs her clients pay for this inefficient administration of the criminal legal system.

She represented a man who was experiencing houselessness charged with possession of a stolen vehicle, who was found sleeping in an unlocked car after seeking refuge there from the bitter winter cold. In the nine months that it took for the prosecution to agree to resolve the case with a guilty plea for a misdemeanor, Alonzo said her client relocated out of state, found full-time employment, and established stable housing in a sober living environment.

But in what Alonzo found to be an emblematic example of the inefficiencies in how the PAO manages felony cases, her client was required to return to Seattle for administrative booking before they could finalize the plea agreement – a $900 expense for the client’s mother to fly him back to the city where he struggled with substance abuse, all so the client’s fingerprints could be collected in a King County facility rather than in any police department or jail in Texas.

Included in the tidal wave of low-level felony filings are cases like one that attorney Reid Burkland eventually convinced prosecutors to dismiss, but in his opinion should never have been filed in the first place.

Prosecutors had charged Burkland’s client with Assault 3 against a police officer, alleging that the client tried to run over the police officer who had woken him up after approaching him in his car. In the discovery materials Burkland reviewed, video footage of the incident showed the exact opposite of the altercation described in the prosecution’s charging documents.

“[The video] showed the police walk around his car with my client asleep inside. It caught them on audio talking about how they were going to try to surprise him, to let them search his car because they thought they saw drugs inside. It showed them positioning their police car about three inches from his front bumper, specifically so he couldn't drive away,” Burkland recalled. “It showed them pulling the door open, starting to scream at him, and within about three seconds, assaulting him, leaning all the way into the car, punching him, and then dragging him out of the car and dumping him in a puddle while he is screaming.”

Once Burkland got the prosecutor assigned to the case to review this footage, the charges against his client were dropped. He emphasized, though, that this footage did not come from investigatory work from anyone on the defense team – it was available to the prosecutor who decided to file the charges initially, who could have declined to file charges had they reviewed the footage prior to making that decision.

While a dismissal represents an excellent outcome for the client, attorney Hana Yamahiro echoed her colleagues’ frustration with the apparent lack of concern for the toll a pending felony charge takes on the people she represents. One of her cases last year was dismissed the day before trial, wasting countless hours of work over months that she could have spent on any of the dozens of clients also counting on her to defend their liberty.

“We spend a ton of time preparing cases that will inevitably get dismissed and the State realizes that long before they communicate it to us,” Yamahiro said. “It can feel like they are waiting for our clients to make mistakes, be put back in jail, and then take some kind of plea deal they don’t want to take just to get out.”

“One of the best moments of my whole life”

When a case does proceed to trial, especially when the case involves a serious felony, it often represents the culmination of years of work by one of DPD’s comprehensive defense teams. In Kai Light’s case, a client of attorneys Vince Hooks and Liza Parisky who was ultimately acquitted of a homicide charge, it took more than three and a half years of waiting in jail to get his day in court.

Kai Light embraces his parents following his acquittal on a homicide charge at trial

Parisky and Hooks both noted that cases like Kai’s take an immense amount of time and resources to prepare, including significant funding for expert witnesses and the crucial assistance of mitigation specialist Bekka Sartwell. With those resources and the support of their colleagues who took on additional work to create time for Parisky and Hooks to work up their case, the defense team successfully convinced the jury in Kai’s trial that the prosecution hadn’t met their burden to hold Kai responsible for the death of another young person.

“Walking him out of jail into his parents’ arms was probably one of the best moments of my whole life,” Parisky said when reflecting on the moment the jury came back with a not guilty verdict.

But she also expressed frustration that Kai likely spent far longer incarcerated pretrial than he should have due to the need to balance other clients’ immediate needs against the longer-term work of investigating a murder case.

“There is no question that the only reason this case took three and a half years is because of our caseloads,” Parisky said. “That's a fact.”

Systemic Reform Driven by Clients’ Experiences

In addition to representing individual clients, DPD advocates for systemic reforms to the criminal legal system that chip away at the unfair advantages granted to prosecutors at every stage of a criminal case. Last year, we succeeded in amending a court rule to grant more equitable access to discovery materials, passed legislation to keep more cases involving young clients in juvenile court, and preserved protections against the admissibility of unconstitutionally seized evidence in a case before the Washington State Supreme Court.

By convincing the Supreme Court to amend CrR/CrRLJ 4.7 so that clients to retain redacted discovery outside meetings with their attorney, DPD ended an inequitable practice where prosecutors routinely conditioned early plea agreement offers on waiving access to redacted discovery in a case. With DPD’s amendment to the court rule in place, clients can now review redacted discovery on their own time and make fully informed choices when deciding whether to accept a plea agreement.

DPD developed and helped pass HB 2217, expanding juvenile court jurisdiction to allow more cases involving alleged offenses committed before a client turned 18 to be resolved in juvenile court. The department drafted the bill in response our attorneys having to litigate extensively to bring cases involving conduct that occurred when the client was under the age of 18 back to juvenile court from adult court when the juvenile court did not extend juvenile court jurisdiction. Other changes in the bill make it more likely that serious charges that are eligible to be declined to adult court will instead be adjudicated in juvenile court.

Finally, in State v. McGee, no. 102134-8, the Washington State Supreme Court upheld strong privacy protections under Article I, Section 7 of our state constitution. The Court held the attenuation doctrine did not allow police to apply for a warrant using tainted evidence, even when police claim new circumstances “lend new significance to the knowledge” gained from the tainted evidence.

After Mr. McGee’s first trial with privately retained counsel resulted in a hung jury and a mistrial, DPD attorney Zachary Brusseau substituted in for Mr. McGee’s retrial. He moved to suppress all evidence obtained from the numerous warrants that included information obtained from an earlier illegal traffic stop, arguing that there was not probable cause for the warrants without this tainted evidence.

The trial court denied the motion, finding the evidence in the warrants was sufficiently attenuated from the illegal stop. The Court of Appeals disagreed and vacated Mr. McGee’s murder conviction.

The Supreme Court affirmed, finding the State failed to “demonstrate any superseding event that produced new evidence used in the warrant application, only a new reason to make the illegally obtained evidence useful.” By identifying and litigating this winning issue, Brusseau preserved the strong privacy protections afforded by Washington’s state constitution and prevented a dangerous expansion of the attenuation doctrine that would have negatively impacted DPD’s current and future clients.

Misdemeanor Defense: Counseling Clients Through Challenging Circumstances

Zulen Pantoja-Ortega, an attorney in DPD's district court practice.

In both King County District Court (KCDC) and Seattle Municipal Court (SMC), DPD’s lawyers and professional staff collaborate to provide clients facing misdemeanor charges with remarkable representation in service of their stated interests. These charges carry significantly harmful consequences for our clients and are often their only connection with the criminal legal system.

Simply having a pending criminal charge against them can cost DPD’s misdemeanor clients employment opportunities, destabilize their housing, and threaten their immigration status. Now that the King County Jail has lifted booking restrictions for many low-level misdemeanors, our clients face the additional risk of job loss and a resulting eviction if they are incarcerated on unaffordable bail pre-trial.

The reality that many of DPD’s misdemeanor clients have no or limited prior experience with the criminal legal system presents an additional challenge for this work, especially when representing clients who immigrated to the United States as adults or grew up in non-English-speaking homes. Attorneys like Ami Nguyen, whose parents immigrated from Vietnam and had limited English proficiency, are often the only person in a misdemeanor courtroom ensuring the person facing criminal charges understands the system trying to restrict their liberty.

“I often have to back up and explain the basics of the criminal legal system in order for [my clients] to even remotely understand what a probable cause hearing is,” Nguyen said, expressing frustration with judges’ and prosecutors’ lack of patience in cases where her client’s native language is not English. “When [a judge] gives me only eight minutes to meet with a client who needs an interpreter, that is out of touch with reality.”

“There was always some stranger who helped us”

Nguyen’s commitment to her clients, like many of DPD’s staff, is rooted in her personal experience of the criminal legal system’s impact on her family. Raised in a community predominantly composed of other immigrant families and defined by poverty, she saw her brother convicted and imprisoned for years for alleged conduct that happened when he was just eighteen years old.

The kindness and support her family received from strangers working on her brother’s case when navigating the system to support him through his trial and incarceration changed the trajectory of Nguyen’s life, inspiring her to devote her legal career to serving others facing similar challenges. Because of that support, Nguyen said her brother successfully advocated for parole and eventually the end of any state supervision of his life in their native California, where he now has a family and works as an electrician.

“There's so many of our clients who don't have any support, and so we become even more important to them,” Nguyen said. “Through the experiences I had, there was always some stranger that helped us, and yes, that was their job, but they could also have chosen to do something else.”

Like Nguyen, attorney Zulen Pantoja-Ortega has a personal connection to DPD’s clients for whom English is not their first language. Her parents immigrated from Mexico, and she also witnessed how language barriers for fellow native Spanish speakers created barriers in accessing essential government services. When she first joined DPD as a legal assistant in 2019, Zulen said the experience of interpreting for attorneys, investigators, and mitigation specialists working with Spanish-speaking clients opened her eyes to how impactful a quality public defender could be in the life of someone from her community.

Now, as a newly minted lawyer in DPD’s district court unit where most charges involve allegations of driving under the influence, Zulen litigates to protect her clients from discriminatory treatment by law enforcement when a language barrier impacts their ability to understand instructions during a field sobriety test.

“I have quite a few cases where I’ve reviewed discovery and it’s very clear that the person doesn’t speak English and troopers are not doing anything to try to effectively communicate,” Pantoja-Ortega said. “There’s no language line access or calling another trooper [to translate].”

Claire Beckett, another attorney working KCDC, said that the opportunity to litigate extensively in DUI cases drew her to seek a rotation to her division’s district court unit. DPD provides ample funding for expert witnesses, which she said makes a world of difference in a public defender’s ability to advocate for a client facing potential revocation of their driver’s license and consequently, the ability to provide for themselves and their families.

Beckett’s intuition is borne out in system-wide data analysis of outcomes for DUI cases in King County: DPD reviewed a random sample of cases involving a first-time DUI and found that DPD attorneys were unlikely to plead their clients as charged and would instead push for trial.

Revival of Failed Carceral Policies Drives Disorder in Seattle Municipal Court

Marissa Miller, an attorney in DPD's Seattle Municipal Court practice.

In Seattle Municipal Court (SMC), 2024 represented a reversal of recent reforms to the misdemeanor criminal legal system in favor of reviving failed policies and a renewed focus on jailing people accused of low-level, non-violent offenses. But even as the Seattle City Attorney’s Office (SCAO) filed more and more misdemeanor charges in SMC, data analysis from both DPD and SCAO revealed that nearly half of those charges filed resolved with a dismissal.

Last year, DPD analyzed every non-DUI, non-domestic violence charge filed in SMC from February 7, 2022, to February 29, 2024. Of the 13,148 charges in that sample, 4,584 were dismissed without a corresponding guilty plea on a related charge, deferred prosecution, suspended sentence, or stipulated order of continuance. In at least 1,042 instances where someone was arrested or booked into jail for allegedly committing a misdemeanor, prosecutors did not end up filing a charge based on the allegation.

Even when the harm of a criminal conviction is avoided, pre-trial detention on unaffordable bail or even a brief stay in jail after arrest can cause significant harm. Because the jail must independently verify any prescriptions someone incarcerated has before providing them with medication and that process takes time, people who only spend a few days in custody frequently do not get the medicine they have been prescribed during their incarceration.

Yujin Maeng, an attorney working in SMC, recounted the damage that being booked for criminal trespass inflicted on an elderly client of hers. “Despite having a valid prescription and being booked with [his medication] on him, he's gone to the emergency room a couple of times for potential strokes related to not being able to have his medication while he's been booked,” she said.

For supervising attorney Vincent Hooks, the coercive nature of pre-trial incarceration on low-level misdemeanors puts undue pressure for clients to agree to plea deals instead of fighting their cases. “Incarceration puts [our clients] in a desperate situation, and a desperate situation results in desperate choices,” Hooks said. “It unfairly punishes our clients in ways that I think that certainly individuals who have private counsel don't have to suffer the same way.”

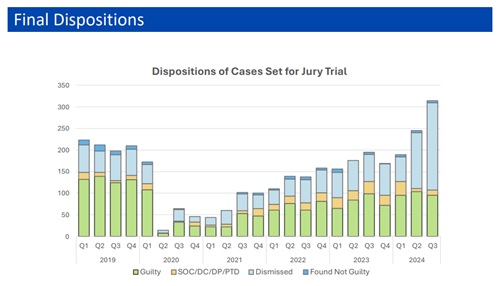

Data from the Seattle City Attorney's Office 2024 Q3 Report

When clients do choose to take their cases to trial, the SCAO’s own data for 2024 show that they were more likely to have their case dismissed than receive a conviction.

Attorney Melissa Miller recalled a particularly frustrating case where she got a case dismissed on the eve of trial in what she believes is a typical example of the disorganization at the SCAO driven by the office’s flood of filings. Her client was accused of an assault against a fellow resident of his senior living facility, but when she and her defense team began interviewing witnesses, it became clear to her that the SCAO had not turned over critical records in discovery – including notes from the detective who investigated the case showing the alleged victim’s repeated inconsistencies in interviews.

Once she interviewed that detective with only a week until trial was scheduled to begin, Miller discovered that the officer had sent their interview notes, medical records containing exculpatory evidence, surveillance footage of the alleged assault, and recorded statements of the alleged victim to the SCAO. Miller had received none of those records even though the SCAO received them more than seven months prior.

Miller got her client’s charges dismissed due to the prosecutor’s misconduct but pointed out that the dismissal only came after months of work on the case that she could have spent helping her other clients. “I worked so many hours, and we have an investigator do so many hours of work before we got to that interview,” Miller said. “I had to write all these motions as a result, and every brief is 30 pages. That’s time we can’t get back.”

Standing Up for King County’s Most Vulnerable Youth

DPD defense teams represented more than 800 clients in juvenile court in 2024, a surge in filings against youth beyond what was “normal” prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The spike in prosecutions against youth reversed what had been a multi-year trend of reducing reliance on the juvenile legal system as a mounting body of research made clear that involvement in the system often results in higher rates of recidivism and worse long-term life outcomes.

In 2024, the King County Prosecuting Attorney’s Office (PA0) filed 30% more charges than in 2023 and youth sometimes spent long periods of time in custody while their cases were investigated and negotiated because they faced long juvenile prison sentences. Supervising attorney Sarah Batson noted that the juvenile facility is “not designed to be a long-term facility, and so you are dealing with kids who are sitting in a place that is not designed for this for months, or even years at a time. It’s just been a challenge.”

The attorneys Batson supervises work with mitigation specialists and investigators to convince prosecutors to reduce or dismiss charges, find alternatives to pre-trial incarceration, and fight the State’s case at trial.

Unstable Housing and Unmet Basic Needs are Common Among Youth Clients

For Batson, the defining trend of 2024 was the increasing frequency of young people being held in jail prior to trial – and the impact that months of incarceration have on the relationships DPD attorneys try to build with their juvenile clients. Despite efforts from the staff at the youth jail to facilitate educational or rehabilitative programming for incarcerated youth, fluctuations in staffing amid the spike in the number of youth held there frequently results in kids spending too much time alone in their cells.

“Young people who get stuck in the jail for a long time make worse decisions about their cases,” Batson said. The coercive pressure of incarceration, in Batson’s view, leads to some clients agreeing to terms to get released even though that their basic needs remain unmet following system involvement, making it hard for them to follow probation conditions.

Batson recalled one remarkably resilient client’s case as an illustration of how material supports, not the threat of punishment, can allow a young person to change the course of their life after system involvement. Her client was arrested after fleeing an abusive home life and ending up homeless on the streets of Seattle. After Batson helped her enroll in AmeriCorps as part of securing a positive outcome in her case, her client is now on a path to a lifetime of meaningful employment as a licensed welder.

When a youth is experiencing homelessness, kids “need a place to go and have caseworkers, people who care about them and mentor them like a parent or family member,” Batson said, reflecting on the lack of community-based options for clients like hers who need counseling or other support dealing with a traumatic past.

Exposing a Failure of Constitutional Proportions in Washington’s Youth Prison

After learning of the deplorable conditions awaiting DPD’s youth clients sentenced to Washington’s youth prisons operated by the Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF), attorneys in the Director’s Office filed personal restraint petitions on behalf of several former clients incarcerated at DCYF’s Green Hill School demanding immediate action to remedy the dangerous overcrowding.

“When we learned that incarcerated youth were kept in their cells so often and for so long that they were provided plastic containers to relieve themselves in due to a routine inability to access a bathroom, we had to act,” said Katie Hurley, DPD’s Special Counsel for Criminal Practice and Policy. “The State has an obligation to provide incarcerated youth with programming and humane conditions while imprisoned; the experiences of our clients at Green Hill revealed the State’s unequivocal failure to honor that obligation.”

After DPD filed these petitions, DCYF moved one of the incarcerated youth DPD represented out of the housing unit where young people were kept in solitary confinement for the vast majority of the day. DPD’s litigation also spurred an unprecedented level of transparency from DCYF on their facilities’ limit for how many young people could be safely incarcerated.

Following the admission that it had dangerously exceeded the limit of how many young people could be safely incarcerated at Green Hill, DCYF temporarily halted admissions at the facility on July 5, 2024. Even after resuming admissions a month later, the agency acknowledged its youth prison remained “significantly above capacity” in a press release announcing the decision.

In parallel with the department’s litigation strategy, DPD’s policy team worked with community-based organizations to craft a legislative solution to the determinate sentencing scheme ultimately responsible for much of the overcrowding at Green Hill. Under the bill DPD helped write, judges would have more discretion to allow adjudicated youth to serve their sentences in local alternatives to the state’s youth prison.

The legislation also included a provision for judges who sentence a youth to imprisonment in DCYF custody to hold a review hearing where the young person would have an opportunity to report on the conditions of their incarceration and earn early release through demonstrated rehabilitation.

“Filing a lawsuit should not be required for attorneys and judges to have an accurate understanding of what life is like for young people within the walls of a DCYF youth prison facility,” Hurley said. “No young person should ever have to live in the conditions our clients have experienced at Green Hill.”

Helping Families Shape Their Future

Colin O'Brien, a family defense attorney at DPD.

In all four of DPD’s divisions, defense teams work to zealously advocate for parents and children over the age of 12 entangled in the family policing system. In partnership with their clients, these public defenders strive to keep children in their parents’ care, reunify families torn asunder by state intrusion, and litigate complex and novel intersections of various bodies of law to minimize the surveillance and paternalism imposed disproportionately on low-income Black and Indigenous families.

“In criminal defense, the consequences for the client are immense about their future, but the work is all about the past,” said attorney Maddie Morrison, reflecting on what she finds most rewarding about representing parents and children in dependency cases. “In family defense, you are helping someone shape their future.”

2024 was also the first full year that courts implemented the Keeping Families Together Act’s (KFTA) which provides a more protective standard for emergency removal of a child from their parent’s care.

As DPD’s public defenders leveraged the law’s enhanced protections against the trauma of unjust emergency removal of a child from their parent’s home to keep their clients’ families together, our policy team faced arguments for the law’s repeal in the state legislature. However, lived experts, doctors, and drug policy experts formed a strong coalition against repealing the law and instead enacting clarifying legislation to make sure that removal decisions involving allegations of fentanyl use are based on guidance from public health experts instead of a moral panic.

“Walking the path together”

At 72-hour emergency shelter care hearings, dependency trials, and termination trials where the state seeks to permanently end a parent’s legal claim to care for their child, DPD’s defense teams go beyond providing excellent legal representation – they ensure each client feels supported throughout the process and preserve their client’s dignity while living under the state’s microscope. For attorney Henry Wiggins, the long-lasting nature of the attorney-client relationship fosters a sense of being embedded in the client’s family dynamic.

“There’s something rewarding about watching a family that’s been in crisis, that’s been in tumult, get to a place where they're not ruptured any longer and the children aren't outside of the parent’s home,” Wiggins said. “Relating to the people I’m representing, holding each other’s hands, so to speak, and walking that path together with the family through their crisis is a big part of family defense.”

Wiggins takes pride in the positive outcomes his negotiations with the Department of Children, Youth, and Families (DCYF) create for his clients, but noted that his clients would often be much better served by a “softer landing place” that offered the same material supports without the specter of having their children taken from their custody.

Colin O’Brien, another family defense attorney at DPD, recalled a recent client’s case that illustrated the enormous hurdles parents living in poverty must jump through to get the assistance they need to provide a stable and safe home for their children: commuting via public transit for more than an hour each way for each of this client’s three weekly visits with his children, calling more than 40 apartment complexes to find somewhere that would accept the housing voucher DCYF provided, all while attending intensive outpatient treatment three times each week, and a weekly parenting class that takes up several hours.

“Of course, that’s nothing to him because he really wants to be with his kids,” O’Brien said. “But when you factor in a lot of the other barriers that our clients face that mostly stem from poverty, it becomes almost insurmountable at times.”

Despite those challenges, O’Brien said he finds his clients’ determination inspiring. “I’m always really heartened when I see clients who are really willing to do anything to get their kids back, and I see how hard they fight to remain in their kids’ lives. It motivates me to do everything I can to try to ease that burden for them.”

As a parent herself, Morrison knows the profound difference her advocacy can make for her clients. “There is nothing that approaches the joy of being able to tell someone, ‘You can go get your baby girl right now, today, at four o’clock.’”

Washington’s Fentanyl Crisis Clouds Implementation of Family Defense Reforms

Though the practice of family defense differs significantly from public defenders’ criminal practice, reforms to the family policing system are just as vulnerable to the cycle of backlash that typically follows any meaningful criminal legal system reform. In 2024, DPD partnered with legislative champions to defend key provisions of the landmark Keeping Families Together Act from repeal in the face of misinformation that incorrectly blamed the reform for the tragic deaths of several young children whose parents fell victim to the ongoing fentanyl crisis.

Tara Urs, DPD’s Special Counsel for Civil Practice and Policy, helped draft the KFTA and worked with community-based organizations to secure its passage in 2021. “Not only was the text of the law based on the language of the Indian Child Welfare Act, but it was also inspired by the same values: a recognition that family separation harms not just children, but communities, and generations,” Urs said.

Despite a two-year wait for implementation to facilitate trainings for judges and DCYF staff on the new legal standard, it became clear in 2024 that additional guidance specific to the ongoing fentanyl crisis was needed. DPD and its community partners provided lawmakers with constructive feedback on SB 6109, which ultimately passed the state legislature and provided funding for training and instructed judges to rely on public health recommendations when evaluating the risk that fentanyl poses to children.

Ultimately, the bill reflected what Urs told KIRO7 the twin objectives of the KFTA: “The goal was to ensure child safety and also to prevent unnecessary removal.”

Preserving Clients’ Autonomy in Involuntary Treatment Act Court

Sarah Tietz, an attorney in DPD's ITA practice.

When the state seeks to compel someone to remain in a hospital to receive treatment for a mental health condition against their will, a DPD attorney is the only person they can rely on to fight for their stated interests. These commitment proceedings under the Involuntary Treatment Act (ITA) have the potential to force someone to stay involuntarily in a psychiatric facility for anywhere from 14 to 180 days without the freedom to leave or direct their own care.

More than 4,000 people depended on a King County public defender’s representation in ITA court in 2024. Our attorneys, in collaboration with DPD’s mitigation specialists and other professional staff, opposed petitions to keep their clients confined in a treatment facility, negotiated to secure less restrictive alternatives to forced hospitalization, or advocated for continuances to give clients additional time to engage with their care and convince the state to agree to an uncontested release from the hospital.

The high-volume nature of ITA practice presents inherent challenges, as attorneys often only have three or four days between being assigned a client’s case and the first hearing where their client’s liberty is at stake. Even amid these circumstances, attorney Katie Morris said she enjoys working with ITA clients. “Most of the time, the client can understand their options for their hearing and what the potential consequences are,” she said. In her experience, clients appreciate having someone involved in the process whose only loyalty is to preserve their autonomy.

A Cycle of Hospitalization

Attorney Sarah Tietz, another public defender practicing in ITA court, believes the flood of filings in ITA court in 2024 can be traced back to decades of under-investment in community-based mental health care. After large-scale state hospitals for people with psychiatric care were decommissioned more than forty years ago, the shortage of outpatient mental health services leaves many of her clients with serious mental health conditions cycling in and out of involuntary treatment.

“What we need are social workers and case managers, who can go to people to give them their medication and take them to their appointments,” Tietz said. “But instead, we have people who just decompensate to the point where the only thing they can do is go to the emergency room and then they're treated for maybe a week before they are discharged out. They end up back where they began, and that’s where you see the cycle of hospitalizations, because they’re never really getting set up for success.”

DPD’s mitigation specialists endeavor to craft release plans for clients leaving the ITA system, but the shortage of available resources for people who need substantial support to live independent, fulfilling lives often confounds their best effort. “I’ve had clients who were supposed to go to a certain shelter or a certain place for a bed, but that’s not available by the time they arrive, and so they’re out on the streets,” Tietz lamented. “All these moving parts have to line up perfectly so that this client can be supported all the way through, and if one piece is gone, the whole plan falls apart.”

Due to the scarcity of supportive housing, even clients who have their own financial resources can cycle in and out of ITA court.

Morris recalled one client, a former professor whose mental health condition manifested after retirement, who spent six months in a hospital waiting for a supportive housing placement that would accept him even though his retirement savings meant he did not qualify for Medicaid. He left the hospital without supportive housing and is now back in ITA court while also facing eviction from his apartment.

Repeatedly cycling through the adversarial process of involuntary commitment harms clients’ long-term chances of successfully managing their conditions, as it often pits beleaguered family members against the person in need of care. “I deal with a lot of family members who are just at their wits’ end,” Tietz said. “They don’t know what to do. They’re desperate for help.”

“I have a client who is 24 years old and has been ITA’d 20 times already,” Tietz explained, noting that the client’s parents do their best to care for their son but managing his schizophrenia requires more expertise and resources than they can provide. “Now their relationship has really soured because it has become confrontational, and the client no longer believes it is in his best interest to engage with his mom and dad.”

Capacity Constraints Threaten to Compromise Effective Representation for ITA Clients

The continued over-reliance on the ITA process to respond to acute mental health crises in King County finally crossed a tipping point for DPD’s ability to provide representation to clients in ITA court in 2024.

Both the Washington State Supreme Court (WSSC) and Washington State Bar Association (WSBA) recognize that attorneys should represent a maximum of 250 ITA clients each year and those case assignments should be reasonably distributed throughout the year. In April, however, DPD had exhausted our attorneys’ capacity to accept new case assignments for that month and advised the King County Superior Court of the department’s inability to accept new ITA cases without violating these standards.

The torrent of ITA filings continued in May, when DPD’s attorneys again reached their limit to accept cases, and the Superior Court issued orders for DPD to appoint counsel in dozens of ITA cases in violation of the WSSC’s and WSBA’s caseload standards. DPD complied, but also appealed the orders to the state Supreme Court seeking enforcement of the standards and protection for our attorneys’ ability to provide effective representation to their clients. In November, the Supreme Court accepted review of DPD’s appeal.

While the outcome of the litigation remains uncertain, the effect of the unacceptably high caseloads for DPD’s ITA attorneys is clear. Both Morris and Tietz agree that the last-minute nature of the court-ordered appointments leave attorneys with much less time to establish trust with their clients before hearings. On top of the additional strain on a challenging attorney-client relationship, the heavy caseloads take a toll on the attorneys themselves.

“We’ll be in trial for a few hours each day, sometimes all day,” Morris said. “We’re still getting new cases where we have to make contact with the clients within 24 hours and prepare for our other cases.”

Opposing a Lifetime of Isolation for Clients Who Have Served Their Time

Washington is among a minority of states that allows the government to petition to civilly commit someone convicted of a sex offense purely on the possibility that they might re-offend. A small but dedicated unit of public defenders called the Special Commitment Unit (SCU) at DPD fights those petitions on behalf of clients locked away within the Special Commitment Center (SCC) on McNeill Island, where hundreds of people are either indefinitely confined or await a trial that examines their entire life to determine whether they meet the state’s definition of a “sexually violent predator” (SVP).

Devon Gibbs, who has represented clients held at the SCC since 2009, sees the work as essential to protecting everyone’s fundamental rights. “Our clients are not even seen as human, so it’s easy to take away their rights,” she said. “I feel like I’m on the front lines that if rights start to crumble in this practice, it’s easier for them to crumble elsewhere in the legal system.”

Gibbs does not believe the clients she represents deserve the stigma that comes with being labeled an SVP. “For the people I’m representing, it’s not about whether they’re guilty or not. That’s usually a decided question,” she said. “My clients are usually elderly and infirm and have their own mental illnesses.”

Clients facing commitment at the SCC have already completed typically lengthy sentences for offenses committed decades ago. Instead of allowing them to return to the community, the state’s petition for their indefinite commitment culminates in a trial that covers a client’s entire lifetime. Because the proceeding is a civil matter, Gibbs’ clients lack many of the procedural protections to which a defendant in a criminal case is entitled.

Gibbs and her colleagues often spend up to a year preparing for a trial due to the wide range of potential evidence available to the state – including compulsory videotaped depositions of their clients by prosecutors. Through detailed release planning, testimony from expert and character witnesses, and combing through tens of thousands of pages of discovery for helpful bits of evidence, staff in the SCU endeavor to convince a jury that their client deserves a chance to prove himself capable of living safely and independently in the community.

Despite the challenges, Gibbs said she finds the SCU to be very rewarding work where she gets to develop lasting connections with her clients.

“I really like getting to be a part of [my clients’] story and show the world that they can get out there and be safe in the community,” she said. “I have known many of my clients for years and years, and I keep in touch with them even when they’re released. They are far more sympathetic than people want to believe.”

Centering the Humanity of Our Clients by Capturing Each Person’s Unique Story

Katie Leifer, a mitigation specialist at DPD.

In each division, DPD’s mitigation specialists put their training in social work to use cultivating relationships with clients in order to capture all the circumstantial factors that led to their involvement in the criminal legal system. Through a combination of motivational interviewing and combing through records of prior treatment providers, mitigation specialists create compelling social histories and mitigation reports that DPD’s attorneys rely on in advocating for compassionate decisions from prosecutors and judges in that client’s case.

“It’s really rare for our clients not to have some sort of childhood trauma,” said Katie Leifer, a mitigation specialist who primarily works with clients in mental health court. Despite their challenging pasts, Leifer’s experience working with DPD’s clients is defined by their kindness. “Clients are consistently so kind to me and so thoughtful. I’m struck by that, over and over again, because I think it’s so different than what people would assume.”

Although many mitigation specialists have advanced training in social work, the work they do for DPD’s clients does not substitute for the lack of social service providers in the community. “I’m not a case manager,” Leifer said, reflecting on the challenging nature of not having the ability to make direct referrals to housing or other services that her clients need to stabilize. “Everything I do has to be tied back to [the client’s] legal case and legal outcomes.”

Incarceration Impedes Clients’ Treatment and Recovery

For clients struggling with substance abuse or other mental health conditions, the widespread belief that jail can serve as a “tool” to compel them into treatment does an immense amount of harm in the opinion of experienced mitigation specialists like Kyle Ankeny.

“In the 15 years that I've been doing this, I've only met a couple of people during the course of that time who actually expressed that they wanted to remain using drugs and addicted to substances,” Ankeny said. “The vast majority of the folks that I work with don't want to be addicted. They don't want to have this substance controlling them.”

And yet, the practical challenges of accessing the medical care these clients need while incarcerated often result in someone leaving jail in worse condition than when they were booked. The process of getting medication while incarcerated can often take as long as 30 or 45 days, and if clients are fortunate enough to start medication while in jail, they are released with only a week’s supply of those medications.

“A lot of times releases happen in the middle of the night or in the late evening, so there’s no one [a client] can even see immediately,” Leifer said. “Then whatever happens, happens. [Clients] use or do whatever they can to self-medicate symptoms and then are back in the same position, or worse.”

“An impossible task”

Mitigation specialists do get an opportunity to fill the gap in the social safety net left by a shortage of social service providers when judges set conditions for a client’s release from custody, but frequently encounter the frustrating reality those conditions end up being impossible to meet.

Kyle Ankeny recounted one particularly frustrating example of this dynamic, involving a client in need of intensive mental health care. After two months of work with staff in King County’s Behavioral Health and Recovery Division of DCHS, Ankeny had secured approval for his client to enter into PACT. He had also found housing that would accept the client’s Section 8 housing voucher, so that the client would have stable housing where the medical team could make regular visits and keep the client on course with their treatment plan.

“PACT is like the Rolls Royce of treatment within the County,” Ankeny remarked. “Where else can you find the program where a psychiatrist or psychologist will literally come into your home and see you?”

Despite that level of supervision, the judge in this case denied the petition for release and asked the defense team for an alternative release plan with a more restrictive living environment. “The problem being there’s not anything that’s restrictive, aside from Western State Hospital, which requires [a client] to be not competent or detained against their will,” Ankeny said. “PACT really is the most wraparound, comprehensive program.”

“Now the client’s family, who was in attendance in court, keeps on contacting us, saying, ‘What programs can we get this client into?’” Ankeny recalled, lamenting the gap in understanding between what judges order and the services available to his clients. “It’s a hard conversation to say this judgment is just ordering an impossible task.”

Molly Hennessy, a mitigation specialist who primarily works with juvenile clients, pointed out that the lack of capacity among treatment providers for youth is especially dire.

“I do a lot of referrals to treatment, which has been really difficult, because there are maybe three or four [providers] in the whole state of Washington,” she said. “There are youth and families crying out for help and they’re running into barrier after barrier with systems of support. Then, someone calls the police, and now they’re in the juvenile system and they want this system to solve some of these really complicated problems when it’s just not the appropriate remedy.”

Uncovering the Truth: The Vital Contribution of Investigators in Public Defense

Matthew Huang, an investigator at DPD.

Investigators play a critical role on DPD’s defense teams. They comb through countless hours of body-worn and in-car video, interview witnesses, spot inaccuracies in police reports, and uncover exculpatory evidence. In modern public defense, where any given case can include hundreds of gigabytes of discovery from prosecutors and police, our ability to provide high-quality representation to our clients depends on DPD’s dedicated investigators.

In many cases, a positive outcome for the client can be traced back directly to painstaking work by an investigator. Felony attorney James Keffeler, who worked at a private law firm with only a single investigator before joining DPD, knows the difference that immediate access to a talented investigator can make.

“When I was down in Kent working on misdemeanor cases, one of the investigators and I did a whole scene visit where we got photographs of the whole layout of the location where the alleged incident occurred,” he said. “We did measurements, because it was a court order violation case. Having those resources available to me right away made such a difference in that case. I couldn't even imagine being able to do something similar at my old office.”

Scrutinizing Sloppy Policework

DPD’s investigators come from a wide variety of backgrounds. Journalists, administrative professionals, and even police officers put the skills they acquired in a former profession to use ensuring that the information the state relies on to charge our clients is actually accurate.

Thomas Baker began his career in the armed forces and then spent nearly a decade as a police officer prior to joining DPD as an investigator. Now, he leverages his understanding of police training and tactics to spot when a detective likely cut corners in their investigations. “I think having that lived experience of working the third shift, when it’s 4:30 or 5:00 in the morning and there’s a corner an officer could cut to get off on time, gives me an intuition informed by experience to know when to do that extra public disclosure request,” Baker said.

Baker’s knack for “speaking the language” of the officers he interviews was particularly useful in a DUI case where the attorney he was working with had a suspicion that Spanish-speaking clients were being discriminated against due to their inability to understand instructions during field sobriety tests. By providing the cops with a familiar narrative of staffing shortages to evade individual blame for the practice, he elicited an admission that a lack of interpreter availability led patrol officers to routinely arrest non-English speakers after a single failed test despite offering native English speakers multiple different tests to demonstrate their sobriety.

Not every police error caught by an investigator stems from bias; investigator Matthew Huang recalled a case where identifying a simple, good-faith mistake was essential to securing a positive outcome for the client involved.

The client was charged with burglary, based primarily on an allegation that a witness saw the client fleeing the scene of the alleged incident with burglary tools, including a crowbar. When police pursued him and a co-defendant, who was ultimately never located or identified, the officer who arrested the client could not find a crowbar on his person.

In reviewing the body-worn video of the officer sent back to the scene the next day to collect evidence, Huang noticed that the officer mistakenly failed to include a crowbar discovered with other tools that could have been used in the alleged incident and flagged the omission for the attorney working on the case.

By the time police returned to locate the missing crowbar, it had disappeared. Without that evidence, the state failed to convince the jury that the client was responsible for the alleged crime and the client was found not guilty.

“He was just walking up the street”

For investigator Taylor McKay, having her work lead to a client’s charges getting dismissed makes her feel both thrilled and deeply frustrated. In one especially egregious example of the difference a talented investigator can make on the outcome of a case, the prosecutor who filed several counts of robbery in the first degree against a young boy ultimately apologized to the client in open court when dismissing the charges.

The boy was wrongly arrested while walking up the street near his house on the way to a convenience store to buy some gift cards for a friend he planned to visit on the evening of the alleged incident. At the same time, police arrested several other young people alleged to have committed a series of robberies of convenience stores by following a GPS tracker hidden in one of the bags of cash taken from one of the stores. The unrelated suspects had ditched a car in the same general area where McKay’s client was walking, and police mistakenly assumed he was involved in the alleged robberies.

“Our client was adamant that he was not involved at all,” McKay said. “He was just walking up the street in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Immediately, McKay and the defense team began collecting as much evidence as possible to corroborate the client’s alibi. She interviewed the client’s mother and sister, who provided detailed descriptions of the clothing the client wore on the night he was arrested that did not match anyone on the surveillance footage from the alleged robberies. They also provided a time-stamped receipt for the gift card the client purchased, confirming that he could not have been present at the scene when the robbery allegedly occurred.

McKay also manually plotted the location of the tracking device used in the police investigation down to the second that evening, constructing a map clearly showing the bag of cash was nowhere near the path the client took from his home to the convenience store. “The mapping took me hours to do,” McKay recalled. “This car was going over 100 miles an hour at times, so I had to plot hundreds and hundreds of latitude and longitude points.”

Though the client was eventually able to repair the strain on his familial relationships the charges caused, McKay remains irritated that the prosecutor even filed the charges in the first place. After all, almost all the evidence McKay collected was available to the police at the time of the client’s arrest and the prosecutor’s office could have done the same mapping work McKay did to vet the client’s alibi prior to charging him.

“On the body-worn video, the police officer was discussing that he didn’t even know if he had probable cause to arrest our client, but he was still arrested and charged,” McKay said. “Robbery one is a very, very heavy charge for anyone, but especially for someone of that age.”

These are just a couple examples of how our investigators play a vital role in ensuring our clients receive a rigorous defense. These investigators, through diligent work, exposed false or sloppy policework on which prosecutors relied when filing charges against their clients. They are good examples of the critical role all investigators play in DPD’s defense teams’ ability to deliver positive outcomes for our clients. Without them, public defense in King County would not be anywhere near as successful in ensuring every piece of evidence from the prosecution is scrutinized and fact-checked before a life-altering sentence is handed down.

Administrative Professionals: The Backbone of Effective Public Defense Teams

Saneel Kumar, a paralegal at DPD.

Each of DPD’s divisions relies on experienced legal administrative specialists (LASs) and paralegals to keep clients informed about their cases, upload and redact discovery, coordinate conflict checks, open and close case files, and accomplish a host of other tasks essential to providing exceptional client-centered representation. They accomplished all of these essential tasks in 2024 while adapting to an entirely new case management system mid-way through the year, showing remarkable resilience when the initial user experience promised by the vendor responsible for the system fell short of the department’s expectations.

Unlike the hierarchical structure of many private law offices, DPD’s administrative professionals are organized in their own unit in each division and assist teams of attorneys across a variety of practice areas.

For LAS Rose Batts, that management structure makes the difference in fostering a workplace culture of mutual respect. “I have great conversations every day with our attorneys here,” she said. “I feel like an equal rather than just a grunt filling out paperwork.”

“We are the only ones they can talk to”

When a client calls DPD to get an update on the status of their case, their first point of contact is one of the department’s administrative professionals. These conversations are often the primary means of contact with the outside world for incarcerated clients and DPD’s administrative staff offer them far more than answers to questions about their case; they build rapport with people experiencing their most challenging chapter of life.

“Some of these clients closed off from society don’t even have family members to talk to,” said Suneel Kumar, a paralegal who enjoys the opportunity to provide a sympathetic ear to clients even when he has already answered the question that motivated the client’s call. “I have clients who called on a daily basis, like three or four times a day. Sometimes all they need is somebody they can vent to.”

Still, the frustration clients feel when an ongoing trial delays an attorney’s response to their questions can be difficult to manage at times. LAS Brenda Salinas Garrido expressed appreciation for the support her division’s managing attorney offers administrative professionals in managing the stress incumbent in fielding frustrated calls from clients. “They’re always forwarding trainings that DPD offers for navigating client interactions,” she said. “It’s nice that we do have resources, like the therapist who works with DPD staff.”

Ruby Harlin, who joined DPD as an LAS to help her decide whether she wants to pursue a career as a public defender, relishes the opportunities to solve logistical problems for clients such as making sure they get transported to court if jail staff fail to get them to a scheduled court hearing. Without prompt notice that the failure to appear was due to a logistical issue on the jail’s part, a judge may set over the hearing and leave the client incarcerated longer than is necessary.

High Caseloads Take a Toll on DPD’s Administrative Professionals

The challenges created by the continued flood of filings from the Prosecuting Attorney’s Office are not unique to DPD’s attorneys; administrative professionals feel the crunch of high caseloads as well. As DPD hires more public defenders to absorb the surge of case assignments, each administrative professional ends up supporting more attorneys.

“Without the adequate amount of support staff, bottlenecks crop up and our unit becomes more vulnerable to any individual having a sick day,” Harlin said. “Maybe that means someone doesn’t get their attorney assigned while they’re waiting in custody, and they spend an extra 24 hours in jail as a result. There are severe consequences to things falling through the cracks.”

Even if all the work is accomplished, Kumar has noticed that the increased workload of supporting more attorneys causes delays that can impact the quality of representation attorneys can provide for their clients. “If you don’t get their records on time, then [the attorney] is stuck in a way,” he said. “They’re not able to give the best advice they can to the client.”

Leading the Charge for Revolutionary Public Defense Caseloads

In 2024, our office joined public defenders around the state to advocate for meaningful caseload relief that will, when implemented, begin transforming this work into a sustainable career. In partnership with DPD’s union leaders (locals Teamsters 117 and SEIU 925), we successfully lobbied the Washington State Bar Association (WSBA) to adopt groundbreaking criminal caseload standards for public defenders based on the recommendations from the 2023 ABA/RAND National Public Defense Workload Study – the first bar association in the country to do so.

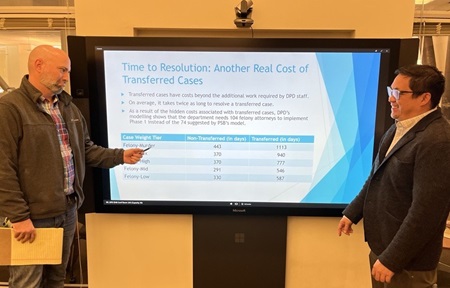

That effort resulted in real caseload relief set to take effect on July 2, 2025. Under the new standards, criminal cases are weighted according to seriousness on a scale of 1 through 8. For example, a theft of a motor vehicle carries a case weight of 1 and most homicides are weighed at 7. Instead of allowing defenders to carry 150 felony cases of any kind which is currently the state caseload limit, the new standards cap the credit maximum at 110 credits in 2025, 90 credits in 2026, and 47 credits in 2027. Mandatory staffing ratios for non-attorney professionals take effect the following year, in July 2028.

Building on that success, our office also led the drive to adopt similarly transformative caseload standards for attorneys in family defense. In September 2024, the WSBA adopted the new standards, which apply equally to child and parent representation and phase in over several years: the hybrid cap will start at a maximum of 45 clients and 60 open and active cases on July 2, 2025 before the caseload standards take full effect on July 2, 2026. The new standards also mandate supervision and training for attorneys in this area and a 1:1 staffing ratio for family defense social workers for each family defense attorney providing representation to parents in dependency matters by July 3, 2028.

Although the Washington State Supreme Court is currently also considering whether to change court rules to codify these standards, DPD has been taking strategic steps to prepare for successful implementation of Phase 1. The King County Code, and labor agreements with DPD’s unions direct DPD to comply with the WSBA’s Standards on Indigent Defense Services. Once fully implemented, the new standards will ease the burden the current system places on all of our public defenders and allow for attorneys the time needed to consistently provide high-quality representation to their indigent clients.

The Human Cost of the Public Defense Crisis

Our staff offered brutally honest testimony in support of the proposed standards during the WSBA’s public comment period on the proposal, highlighting how the outdated caseload standards have made it all but impossible for public defenders to provide constitutionally effective counsel to all their clients. They relayed stories of clients sitting in jail for years waiting for their lawyer to have enough time to work on their case, only to be acquitted once they finally got their day in court.

Reflecting on the cost of the current unsustainable caseloads, attorney Reid Burkland emphasized that even clients ultimately found not guilty pay an enormous price for the delays caused by excessive caseloads – profound harm that he believes should be treated more seriously by prosecutors and other policy makers in the criminal legal system.

“Our clients are already living so close to the margins that going to jail for a day can then cause them to miss work and get fired, then not be able to pay their rent and get evicted,” he said. “It can mean missing family events and missing connection to the community. It can mean being put in an environment that has rampant drug use, and people are then under stress and surrounded by drugs and relapse.”

Burkland also gave an example of the kinds of sacrifice such excessive caseloads require of public defenders and their families: “I remember when my first son was born, there was a stretch when he was an infant where I never saw him awake, because I would go to work and he would still be asleep,” Burkland said. “I would come home from work, and he'd be asleep. I would interact with him on the weekends, but during the week, I wasn't seeing him awake at all.”

Promise of Caseload Relief Inspires Cautious Optimism for DPD Attorneys

For many attorneys like Liza Parisky, the new standards are essential for their ability to continue practicing public defense despite their passionate commitment to the work and their clients. They have watched the burnout well-chronicled in the ABA/RAND study among public defenders nationwide claim too many of their former colleagues to assume they can sustain a long-term career without the significant improvement in working conditions promised by the new WSBA standards.

“I think that the colleagues of mine who have left here largely it's because they just want to do better by their clients than the court system is allowing them to do,” said Parisky. “That just really takes a toll on people.”

Even with the first phase of the new standards not set to take effect until July 2, 2025, the fight to win caseload relief has brought many staff at DPD closer together.

Attorney Hana Yamahiro described the process as a “bonding moment” among the friends she made since moving cross-country to work at DPD, recounting the twin feelings of affirmation and anger brought up by reading both her colleagues’ public comments to the Washington State Supreme Court in support of the standards and those written by prosecutors and politicians opposing their adoption.

“It's certainly obvious that no one understands the work that we do and what we go through except for us.”

Sustainability and Support Mark a Summer of Meaningful Advocacy for DPD’s Interns

DPD’s Rule 9 interns gather outside the Dexter Horton Building in downtown Seattle

Cecilia Atkins, a rising 3L student at Michigan Law, chose to spend her summer internship at DPD largely because of Washington’s unique Rule 9 licensure that allows supervised students to speak on the record. At the start of the 10-week program, she took over a handful of cases from a public defender who rotated into felonies from practicing in Seattle Municipal Court.

Although Cecilia had heard from classmates at Michigan who had interned at DPD that she’d have the support from supervisors and non-attorney staff to provide the high-quality representation her clients deserved, taking on more clients than she’d ever represented in a clinic seemed daunting at first. Then, she started meeting the people whose interests she spent the summer working to serve.

“I had so many concerns about telling [my clients] that I’m an intern, but they have been incredibly trusting. I’ve been lucky to work with so many clients who are incredibly kind people.”

Many of DPD’s 21 summer interns reflected similarly enthusiastic stories of having the opportunity to provide high-quality, client-centered advocacy. They sought release for clients at arraignment, wrote motions seeking to suppress unconstitutionally seized evidence, cross examined police officers, and prepared entire trials. Through it all, they stressed the importance of the support they received from supervisors and line attorneys at every step – not only in giving them the confidence to advocate on the record, but in fostering the camaraderie among interns that helped make the experience so rewarding.

“I couldn’t stop smiling,” said Bradley Marshall, a rising 3L at Seattle University School of Law, thinking back on winning release for a client charged with Assault IV in Seattle Municipal Court. After prevailing on his argument that the scant three-sentence narrative in the police report could not establish probable cause to support the charge against him, he recalled seeing his supervisor and his fellow interns reflecting his beaming grin back at him from the gallery.

Elise Brown, a rising 3L at NYU, also found the collaborative environment at DPD essential in learning the practical skills she hoped to build during her internship – especially in cross examination.

“Cross is much less intuitive than opening or closing; it’s a unique skillset,” Elise said. “It’s really hard to learn things like impeachment without actually doing them.”

Elise reviewed her draft set of questions for every cross examination with her co-counsel, who made time to provide feedback on which lines of attack to prioritize and how to overcome anticipated objections from the prosecution. Then they’d repeat the process after each cross examination with a focus on where she could have let a point go, which Elise said gave her confidence she was improving on an extremely difficult skill.

That dedication to making time for providing feedback on work product also extended to motions and briefs DPD’s interns authored in both felony and misdemeanor cases.

For Tyler Zirker, a rising 3L at Georgetown, writing a motion to suppress evidence obtained from a pretextual stop in a DUI case earned him his “first big win as a public defender” – after the attorney who assigned him the project filed Tyler’s motion, the prosecution dismissed all charges against the client. Following the victory, Tyler said he appreciated how both the attorney of record and his supervisor offered to meet with him to further polish the motion so he could use it as a writing sample in applying for a job in public defense when he returns to campus this fall.

“I want to go somewhere where I can actually help people”

This summer’s class of interns joined DPD just as the department began implementing the WSBA’s newly adopted caseload standards for public defenders. For a generation of law students concerned with the sustainability of a career in public defense, the welcome news of reduced caseloads and consequentially more time to advocate for each client sparked cautious optimism.

“When I talk to public defenders, people love the work but they all talk about burnout,” Tyler said. “The emotional load is very heavy, the caseloads are very heavy, and it’s hard to make it a 9-5. I want to have time for my clients. I want to go somewhere where I can actually help people, and a place that promotes having work-life balance fits that.”

As someone who plans to take advantage of the federal government’s public service loan forgiveness program, Tyler emphasized the importance of finding an office that supports its public defenders in dealing with the burnout inherent in the field. When attorneys have the kind of support that he’s seen during his internship, Tyler said, it empowers them to provide the kind of representation that keeps prosecutors on their toes and hold law enforcement accountable when they violate a client’s constitutional rights.